People Make the World Go Round

On labor, grace, Black women's shit talkin, and...maybe something else

I have been listening to the Stylistics’ 1973 hit, “People Make the World Go Round,” and shedding sweet and bitter tears. The tears have to do with gratitude, indignation, disillusionment, and joy. Also and ironically, I keep learning that artists I loved as a kid are from Philly, the place I now live and love.

Just before Christmas last year, I was outside catching up with my neighbor, Ms. A. She is a Black woman in her 70s, who has lived in her home—directly next to the one I live in—since 1975. She and her husband are not the only ones on this almost entirely Black block who have been here for more than a generation. Many of my neighbors are my grandmother’s age, and their children are my mother’s age. Ms. A is not officially the block captain—Ms. R is—but she runs the block. She has everyone’s phone number, knows everyone’s name, will hide your package if the delivery driver sits it on your porch, will remind you to move your car before PPA comes on street cleaning day, and will talk your ears off if you let her. I often let her. Somehow, she also knows when someone is about to move into an empty home on our city block and can now anticipate the only question I ever care to ask about them, “and yes, before you ask, they Black,” or, “I know what you bout to ask and, they, um, that other kind.” So, when she told me, “I told the girl up the street I’d ask you something. She lookin for somebody to watch her daughter some evenins when she at work,” I was all ears. “Where she live? How old is her daughter?” I asked. She pointed to the Nissan halfway up the block. “She lives up there. The little girl is so smart. I know you like kids. I told her, ‘ask Destiny. She don’t work. Her husband is a doctor.’”

I started laughing and thought I wouldn’t stop. I paused just long enough to say, “Now, Ms. A…you know I work.” She pursed her lips and tilted her head. It’s the same look my entire family gives to playfully say “you lyin.” I giggled, and continued, “You know I work.” She replied, “Well yo car always right there” and she pointed to Di’Avionne, the car I named after Alexis Fields’s character on “Sister, Sister.” “Fair enough,” I told her. “Give the girl my number.”

Of course I work, and Ms. A knows my work requires me to spend long hours in my home in front of books and my computer, or at libraries or, or a cushy but barren office in a university academic department building. She knows I have a couple of degrees from places with names people care about. She has seen me loading my car for art shows and seen me unloading art supplies and books.

She was teasing me, witty as she is. Witty as I am, I interpreted that she was naming different kinds of work. Mine was the kind that looked like leisure, compared to, say, the working single mother she was asking me to help. It also looked like leisure compared to the work she and her husband both do, though they’re in their 70s. Actually, it looks like leisure compared to the work most people in the neighborhood and most Black people in this country do. Compared to the kind of work my mother and aunties do, it is leisure. Scholarly work certainly serves its purposes, but visual artwork, poetry, literary and cultural criticism does not make any world go round in these parts. That’s not self-deprecating; it’s perspective and a sense of humor and being blessed enough not to have my head too far up my ass. Work that is self-determined and allows me to pursue my intellectual interests is exactly what my mother, grandmother, and and aunties wanted for me. Ms. A runs the block and has adult children and grandchildren, but she is not this block’s mother or grandmother by any stretch. Still, I know this life of not-work is also what she wants for me and for the younger women around here. She says as much during our porch conversations.

Trash men didn't get my trash today

Oh, why? Because they want more pay

Buses on strike want a raise in fare

So they can help pollute the air

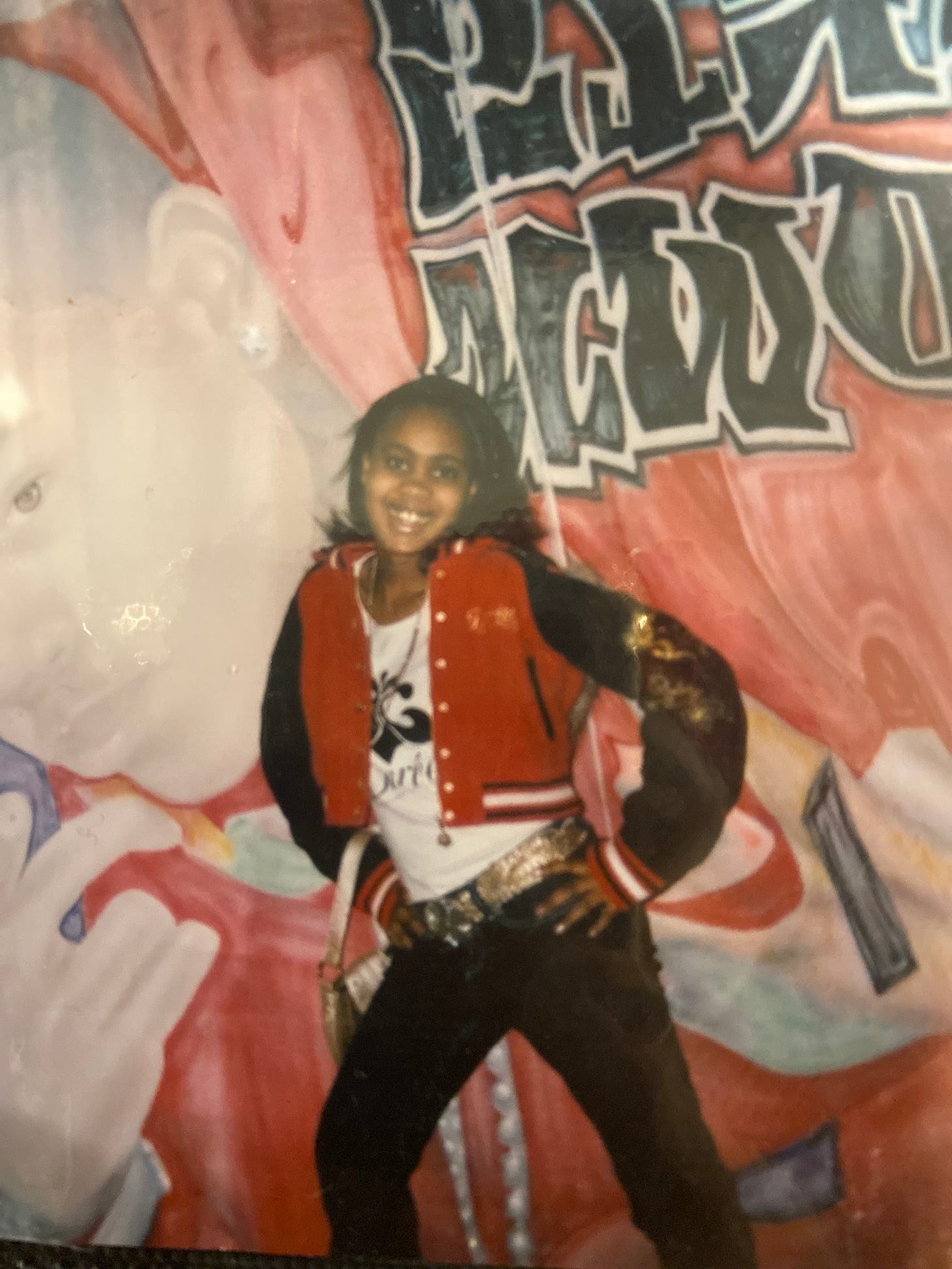

I first heard this stunning song on the soundtrack of Crooklyn, which is a movie that makes me remember my bedroom in the two-family flat on Osage street in St. Louis, which is where I watched that VHS tape over and over. The walls were a pale bisque, popcorn texture everywhere, including the ceiling. The first few notes from that vibraphone at the top of the song once made me feel wistful and wanting. When I hear the song, I can see Troy the Boy with her head cocked to the side, braids and beads hanging. That film babysat me on nights when I waited for my mother to come home from work. She did the kind of work that required her to wipe old people’s asses, but could not cover evening childcare, so I read, drew, played with my Christy dolls, did my homework, and heated up the meals she left for me. Most single mothers I knew did the kind of work that required them to wipe ass or clean, and leave their children at home to look after themselves. The woman up the street from where I live now was trying to prevent her baby from doing what I did.

I would not know until I was an adult that for some people, it was not the norm for an eight year old to be home alone from 4 pm until midnight multiple nights a week. I read once that children whose parents do not have college degrees get fifty percent less of what they call Goodnight Moon time than children whose parents do. That’s not just about money—it’s about the kind of labor one does. I was actually considered sheltered and lucky compared to some of the kids in my neighborhood with whom I liked to play. I never experienced home disruption or surveillance under CPS, my mother and grandmother never suffered from substance use or experienced incarceration—though my father had and died in jail—I had my own bedroom with lots of books and toys and cute clothes, and I went to the public district’s gifted school from Kg-8th grade. When I did live with my grandmother, it was because my mother worked too much and placed me in her care, not because the state had. Where I’m from, this is all a relatively privileged life.

At one point during my second grade year, someone gave us an old TV that only worked to show VHS tapes that my mother placed in my bedroom. Later, I got Crooklyn and Maid in Manhattan on VHS from my auntie’s house to aid me during the nights she was at work. We never paid any mind to the distinction between children’s media and film, books, or TV shows aimed at adults. For the most part, I watched and read what I wanted. I loved Troy’s brooding stare, her pretty name, and those high pitched and airy voices all over the 1970s soundtrack. I was grateful to have the TV and movies at all, since a year earlier, and just after Christmas, someone had broken into our home while she was at work and I was elsewhere, and they stole all our VHS tapes, the DVD player and the DVDs, and the living room TV. This was the second time this had happened.

But that's what makes the world go round

The ups and downs, a carousel

I don’t remember where I was (my memory ain’t shit as far as the short term, sometimes) but recently, I was somewhere up here in the Northeast with other people who have a bunch of designer formal education, and I told the story about what Ms. A said. I was talking to a few different people, and I thought it might invoke a hearty, collective laugh and then some conversation about work and race and gender, but it did not. The people were offended for me. Something about my being an educated and driven woman and how my husband’s job didn’t need to be mentioned. And how all work is real work. I understood the sentiments, but I was bored.

Changing people's heads around

Go underground, young man

People make the world go round

A couple of years ago, I had a falling out with someone with whom I was close. I will call them Kay. I thought about it a ton at first and even did some crying, and then hardly at all, and now I think about it from time to time, but not in terms of “how could Kay say that?”. In the words of Porsha Williams from RHOA, “I’m nobody’s victim, bitch.” In other words, this bit isn’t about my pain or their villainy, I don’t think. They are not a villain. In the most fragile nutshell: they’d forgotten about a milestone that had been a decade in the works for me, one in which I’d invited people to witness and to celebrate. Well, I guess it had been 27 years in the works, and entirely unheard of in my family and neighborhood. For some of those years, they’d mentored me toward that milestone with deep care and laughter. The forgetting wasn’t personal. I forget dates unless I put them in my calendar. I’ve also missed folks’ meaningful events due to work, illness, travel, or even not having the money to go, when the events cost. It was what came after that stung. When they apologized, they offered that I should have reminded them, and should the next time anything big comes up. Worried that they thought they’d been left out of a round of reminders, I told them I did not remind anyone. People had instead reached out to me in the days before, not the other way around. Kay explained that they are busier and work more than most (in comparison to the people who remembered to put the milestone event in their calendar or however they kept up with it), and that they are part of a cadre of people that work for years with no breaks or care. They said my expectations should be reserved for people with leisurely lives. I read their tone as uncharacteristically nonchalant about a milestone—not just that singular event—that my friends of all ages and stages, and who did not have leisurely lives or any of the advantages Kay had and has…..had called “the biggest deal. I expressed how disappointed and hurt I was, but also how confusing it’d felt. They posited that I could have had more grace for them. I didn’t lack grace for the no-show, but I did lack grace for the nonchalance that followed. In that regard, her claim was kind of true. Like lots of Black women and girls, I have been socialized to have too much grace, and usually in the face of disregard. The hard lessons that have come from this have contributed to some hypervigilance, so I have oscillated between too much grace and not nearly enough. Kay had previously advised me to have grace for someone else in a moment of blatant misogynoiristic institutional disregard, so I did not like their use of the word grace during our heated exchange. Plus, in Black cultures writ large, I’ve generally experienced/observed grace as reserved for people Kay’s age (and professional seniority) and older in these kinds of things, but in short supply for younger Black women, and nonexistent for Black girls. I have wondered whether grace is what is meant, or if the term grace is being used as a stand in for, “if I hurt you, don’t say anything about it because you are younger/less senior than me, and people who are not my age peers or professional equals are supposed to unsee any mistakes I might make/never disagree with my words or actions.” Almost the way the term “forgive” is often misused to mean “be quiet and get over it” in the same cultures. Those of us who are told to have grace and forgive the most often receive the least of it, like in that conversation. I felt as though my trying to understand what Kay meant was cast off as the complaints of an angry Black woman—no grace for me. But just because I didn’t like their use of the word or the cultural context from which it comes, and just because I wasn’t receiving any grace, doesn’t mean they didn’t eat me up with that one thing.

Kay’s implicit comparison of our work lives shrunk my disappointment about the original spat. It made their lapse of memory and subsequent indifference seem like a blip leading up to words I never imagined they’d say. They’d been exchanged via text, the worst medium to have any conversation worth having. I insisted upon a phone conversation to gain a better understanding. I desperately hoped I’d misunderstood. They refused to speak any further about it. The person I knew as previously interested in discussing ideas from almost every angle was suddenly curt and disregarding in this conversation that had become about capacity and woman work. More than that, they’d introduced me to a bunch of books and articles over the years about class and social policy in regards to Black women. There was no way they could have meant what I thought they had. Wrongfully, I insisted again on a phone conversation. This time, they not only had no desire to sit on the phone to pontificate with me, but they also had no capacity for the conversation, and that was that. For them.

What Kay likely didn’t know was what “work” looked like for me during that time, or for the entire time they’d known me, for that matter. We often talked about literature, and art, pop culture, and life happenings—both the fun and not-so-fun. I told funny stories and listened to theirs. I showed off the nail art I was wearing, talked about cute clothing items I’d planned to buy. There was never a need to center how hard I worked, how hard it was to not have taken a dime from back home since I went off to college.

In this conversation about work, unlike the lighthearted one with the working class Ms. A, words about work, who worked a lot, and even comparisons about the amounts of work one does in relation to others were coming from someone who was raised by two Ivy League educated parents—and was now wealthy. I was applying for jobs while all out of money to make it to the faraway interviews that wanted me to pay for my own flight, and with an uncertain professional and economic future, and these words came from someone with permanent job security. Unlike that playful conversation with Ms. A, these words were coming from someone whose mother did not wipe ass for 12 and 16 hour shifts, who did not rely upon community organizations like College Bound and LEDA and Trio and the St. Louis Scholarship Foundation to learn how to navigate a college application. From someone who had been a well-connected legacy student at Ivy League undergraduate and graduate institutions, and who had said many things about money and access to which I could not relate. I never faulted them for it or thought about it too deeply.

Wall Street losin' dough on every share

They're blaming it on longer hair

Big men smokin' in their easy chairs

On a fat cigar without a care

I think that is in part because of a Black working class savoir-faire I was reared into that is in the wind all around: honesty about one’s material conditions reflects shamelessness and authenticity, but expression of sorrow about it is frowned upon. And sorrow is distinct from a shrewd scrutiny of one’s own status as a Black person and worker in this wretched place. Conversations in which my folks complained about abuses of power, surveillance, disregard, and low pay at the jobs where they worked on their feet were punctuated with the practical, “but at least I got a job.” It was not kissing up; it was a recognition of how many people around us could not work due to substance addictions, incarceration, untreated and under-treated physical and mental disabilities, or could not find legal work.

“Thirty-two thousand dollars? They paying you all that?” is what my Gammy said when I told her what I’d be making as a graduate student. She was gleaming. It would be more than most people we knew made. Exhalation. So, I never complained about my lack of money, or how much labor I did in extended family responsibilities, because I wasn’t socialized to see sitting on the computer for 12 hours straight for research, writing, Zoom meetings, teaching myself to become a bootleg reading specialist, tutoring 4-6 back to back sessions a night, and then meeting with relatives and attending to my own visual art practice, going back home for summers for child-related familial responsibilities—as hard work, despite the fact that my body told me it was.

But that's what makes the world go round

The ups and downs, a carousel

I was dealing with many of the same things Kay listed that they, too, dealt with. But I had none of the money or stability they had. I also had not come from the relative (it’s all relative, especially for Black people) institutional access from which they’d come in their early life that informed their adulthood. My mother’s high school diploma made her the most formally educated person in my family. In my family and neighborhood, Harvard, Yale and Princeton existed on TV and nowhere else. I read Kay’s words as an unseeing of an obvious and colossal socioeconomic difference between us—both in terms of our respective starting points in life and, separately, where we both were at that time. For myself, I experience chronic fatigue, as well as a separate chronic physical pain issue that is a direct result of not having money (or health insurance) for a period of my life. I also held/hold familial responsibilities that eat both time and money. In grad school, I spent day in and day out offering tutoring services late into the night to be able to afford some of the things I needed to provide. One of the things I was called to provide was paying for a reading specialist or instructor who knew a lot about dyslexia, along with navigating a public school IEP process via years of emails and Zoom meetings. Despite how many hours I tutored, I could never make enough to pay for the number of hours of reading intervention necessary—so I spent an additional few hours a week learning everything I could about dyslexia, about ADHD, and about a variety of literacy building methods to provide this intervention on my own. I went home each summer, both to enjoy my city, and to tend to things. I dealt with multiple young adult relatives who had the kind of legal troubles that cost money and made me shoot awake some nights, worrying about their unsafety and distress. The rest of what I needed to provide or show up for and for whom I needed to do it is not my story to tell and even if it were, I wouldn’t tell it.

I keep the rest of what I do close because telling people what you do for the next person, especially when that next person has less than you do socioeconomically, is rightfully despised in the Black working class culture in which I was socialized. I appreciate that my generation, especially women, are publicly counting multiple forms of care as labor and are naming boundaries around it, but/and I am also appreciative of the fact that the women I come from are so interdependent that naming ones deeds is moot. It has some obvious interpersonal drawbacks that I’ve experienced too many of, but it leaves no room for rugged individualism or isolationism. Additionally, this same culture is one of pride that can easily be misunderstood as shame. I come from folks who have the sort of unceasing belief in their abilities to survive coupled with disgust for haughtiness that they will sleep in a car, motel, or shelter before accepting money or time-eating favors from anyone who would posit themselves as a savant. I share my writing with some of my relatives, who would clock my tea if I ever depicted them as people who cannot take care of themselves without a do-gooder, overstated my contributions or my relationship to financial lack, or positioned them as burdensome.

Every time I have typed in my debit card information or swiped at the register with the flash and flair of my pointy acrylic nails to provide something for a loved one, I’ve felt that heat of golden gratitude at the pit of my stomach—even if it is my second-to-last dime (never ever my last, I’m neither martyr nor masochist). I may as well yell to myself, “We made it, BITCCHHH!” like Mo’Nique did when she came out for her latest stand-up set.

I don’t say this to paint myself as some savant or exception—I’m exactly the opposite. I do not know of any first generation college grads in their twenties who are not somehow supporting elder or younger relatives back home. Nor do I know any who have ever had only one stream of income. I am glad to be part of this club of people who are connected to their people, as care and work and care and work. When we get together, we are talking about art and life happenings more than we are talking about difficulty and labor.

I was introduced to the term “materialisms” in grad school and didn’t know if I was comin or goin. The Black people I knew with the least “materials” (my relatives in St. Louis, my friends of all ages, and my neighbors in West Philly and now South Philly) and had to work to the bone to get them never seemed to talk about their lives, or about Black life in general, in the way that seemed to be the norm in this different, different world than where I came from. Work, lack, hard, and death. My guess is because there is no immediate reference point—there are virtually no white people or wealthy people in their personal networks or personal lives. I knew very few white people growing up, and no wealthy or, separately, professionally prominent people. Plus, my folks were working damn hard to make sure “hard” was not the first word with which they could describe their lives. I am writing more about being Black and working-class reared these days. But I am stewing over every word, not out of shame, but because I know how much embodied, physically and mentally taxing labor went into making sure part of my story never included certain aspects of poverty. So that lack and barely holdin on would never be all I had.

Changing people's heads around

Go underground, young man

People make the world go round

At this point, it’s important to note the age and, in our respective places, professional seniority gap between Kay and I. My own observations about this age gap along the lines of class have been a path to forgiveness and letting shit go. Assuming youth = ease is simply part of upper middle class and wealthy American culture writ large. It’s not specific to Kay. One example I have noticed is in those debates regarding the fight for $15 minimum wage. Some people claim that retail and dining work was never intended for people who are supporting families, but instead for teenagers and early twenty somethings. In my family, in my life, and in the lives of some of my friends from college, grad school, and other parts of my life (the friendships that deepen and stick happen to be ones in which we have been similarly situated as far as socioeconomic origins) young twenty somethings do have what upper middle class people often assume are grown up bills and responsibilities. In my high school and neighborhood, and among the women in my family, many people have one or even two children in their teens. Even our language, broadly speaking, about health centers a linear life of ease to ailing. By 23, my two closest friends and I had all developed chronic physical pain issues that have never subsided or been cured, though we all now have the means of treating them. None of us were on our parents’ health insurance right after college. One spends their twenties financially, physically, and mentally, paying themselves back for being born working class. It’s debt. Again, I am talking about a socioeconomic status that is not just about money, but also about about lifestyle and access. I still don’t make very much and my shit is fragile and uncertain. Kay’d expressed before that when they were at the beginning stage of their career, they were not worried about money. I have worried about money and my own immediate material needs since my teens. I still remember the months-long insomnia and stress-induced stomach pain before the ACT and SAT because I knew those scores were determinants of whether I’d get out of poverty or transition to something just a needle’s eye easier. Now, there are young folks in my life, some of whom are children, some are college students, who have that carefree spirit about them and those glimmering playful eyes, but whose material conditions make their lives significantly more difficult than mine is right now. Socioeconomic status makes everything different.

But even the inclination to compare whose life is harder seems so much more common among the monied and highly formally educated in my life on the Northeast than the folk from which I come, and is nonexistent among my friends who come from low-income families in St. Louis, Atlanta, Chicago, Philly, and other parts. My mama jokes about academic work as fake work, but when she is serious, she has never, not once, told me that her life is harder than mine, even if, objectively, it has been. Nor have my aunties—one has cleaned hospitals for decades and another has cleaned hotels for decades. They all had children when very young, and were all single mothers whose men had been stolen by early death or prison. Recently I asked my grandmother, who worked and was raising two children when she was my age if she thought her life was harder work than mine, “nope, just different.” I don’t think this is entirely true, but I do notice how the women who do more taxing work than me and for less pay, and with less cushy lives all around have never seriously minimized my relationship to work, because it is the relationship they dreamed I’d have. It was my mother who told me, as I finished grad school, “You ain’t had rest since you was like 14. You’ve always had to go go go. Can’t you do something light for a year or two after this?”

Months later, I was in my first semester of my postdoc, and I was researching and writing a bunch, working on some visual art projects, and did not get to teach until the following semester. I wanted to cook a pot-roast on one of those days. I told my mother that months earlier, my pot roast didn’t come out right, and I wanted to get this one right. It was edible, but not nearly as tender, flavorful, and fragrant as hers. I bought a pot roast kit from Aldi. I’m not sure what possessed me to do that, because if someone had told me they bought a pot roast kit from anywhere, I would turn up my nose and tell them that’s for white people. Then, I would assume they mama can’t cook. I asked my mama what she did to hers that made me powerless to the temptation to sneak into crockpot before it was time to eat, and pluck out a piece of potato or, audaciously, a piece of meat. She told me that while I could make everything else just the way she made it, I was missing a key part of her pot-roast recipe. “You not gon be able to make yours like I made mine. I put the stuff in the crockpot and put it on low before I went to work. I came home and it was ready. But you don’t go to work, so you can’t do it like me.” We both cracked up. She think she witty, and she is. “Fair enough,” I told her. I have not attempted pot roast since she said that.

In my formal training in Black Studies and in Feminist Studies at both the undergraduate and graduate level, I was taught that the race and gender of an author or artist should not be a determinant in how we read their work, as long as the work is not in service of whiteness or patriarchy and is “rigorous.” I understood it and took this into consideration most of the time, but never completely bought it, though I always respected the people from which this perspective was coming. That, too, might be a classed orientation: never buying the idea that the work someone produces could be more important than who they are or their lived experiences in this machine. But positionality and lived experience in terms of class can make two very similar statements land entirely differently. A wealthy woman with relatively leftist political leanings—who I did and still do love—implying my friends and relatives live a life of leisure compared to her sent me to angsty tears, and then confusion. But working class Black women joking about reading, writing, teaching, planning, making art, etc as fake labor feels like a hug, says “I am proud of you for not having to wipe ass or stand all day.” I think I can let it go and have a sense of humor about Kay’s words now, too.

Go underground, young man

People make the world go round